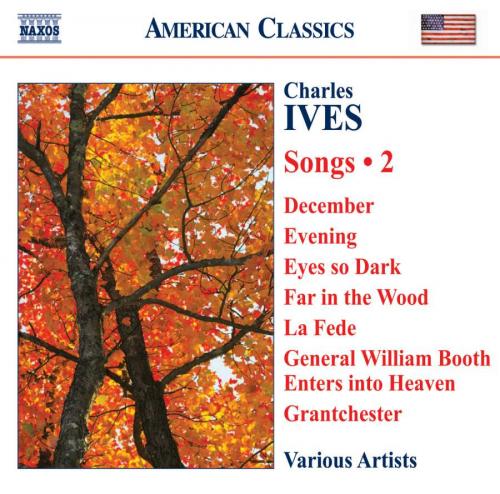

Songs • 2

When, in 1922, Charles Ives published a volume entitled 114 Songs, he was likely drawing attention to the fact that the genre had played a central part in his output. 85 years on and, for all that his wider reputation may now rest on his orchestral, chamber and piano music, it is the songs that represent the heart of his creative thinking. Nor was that initial volume at all comprehensive; Ives having written almost 200 songs, of which this present edition includes all of those he completed. The expressive variety encountered is accordingly vast: indeed, the gradual evolution of Ives’s songwriting, from those that draw overtly on the Austro-German Lieder and English parlour-song traditions to ones that evince an anarchic humour as keenly as others do a profound vision, is surely analogous to the wider evolution of American music over the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Although it would be entirely possible to collate Ives’s songs according to type, the alphabetic approach adopted by this edition ensures each volume (of which this disc is the second) contains a representative cross-section. A considerable range of poets is set (and Ives could be highly interventionist as and when it suited his purpose), including a number of (mainly early) German settings and forays into French and Italian. The temporal distance (1887-1926) traversed by the songs is as little compared to their stylistic diversity or their emotional range.

The extent to which Ives reworked songs throughout his career is considerable, whether substituting a text or reworking the actual music. To this end, songs with a musical or textual connection are crosslinked accordingly (i.e. in brackets at the end of the relevant paragraph).

Undoubtedly one of Ives’s most forceful and demonstrative songs, December (1913) is a setting of Folgore da San Gimignano – in the translation by Dante Gabriel Rosetti - which is designed to be sung “roughly and in a half-spoken way”, so giving this tale of ‘seasonal ill-will’ an appropriate harshness and astringency that never wavers.

A setting of Ives’s own text, Disclosure (1921) is another of the composer’s speculations on the transcendental, its piano writing wholly subservient to the fervency of the recitative-like vocal part.

A further Ives setting, Down East (1919) opens with an ominous preface whose tonal vagueness gives the evocation that follows the sense of a flash-back to a more innocent and less troubling time.

Setting a Baroness Porteous text which reinforces the conviction that it is best to travel in hope, Dreams (1897) avoids being an archetypal parlour song largely through its unexpectedly wide-ranging piano part. One of several songs Ives set simultaneously in German and English, Du alte Mutter (1902) brings a keen nobility to Aasmund Olafsson Vinje’s sentimental text of filial devotion (see also Volume 4, tracks 10 and 25, Naxos 8.559272).

Setting a poem by Heinrich Heine, Du bist wie eine Blume (1897) is an archetypal ‘Lied’ such as might well pass for that of a lesser Austro-German contemporary (see also Volume 1, track 28, Naxos 8.559269, and Volume 6, track 24, Naxos 8.559274).

By contrast the setting of Louis Gallet’s Élégie (1901) is hardly a typical ‘chanson’ in its systematic repetition of phrases along with a measured, even restrained piano accompaniment that suddenly wells up in a central apex of heartfelt emotion, and can certainly be ranked among the most striking and personal of Ives’s earlier songs.

Setting an emotive text of unknown authorship, The Ending Year (1902) is highly fervent in manner and also shares material with other Ives songs (for which see Volume 5, track 35, Naxos 8.559273, and Volume 6, track 17, Naxos 8.559274).

One of Ives’s most perfectly realised songs, Evening (1921) renders John Milton’s verse with telling fastidiousness, while changing its final phrase from past to present tense so as to intensify the rapture.

Setting a pantheistic text by the composer, Evidence (1910) is notable for the way in which voice and piano anticipate each other in an outpouring of gentle ecstasy (see also Volume 6, track 28, Naxos 8.559274).

Another parallel German/English setting, Eyes so Dark (1902) treats William Joseph Westbrook’s translation of Nikolas Lenau such that its emotional ardour feels dampened down (see also Volume 6, track 22, Naxos 8.559274).

A teenage composition, Far from my Heav’nly Home (1893) is a fervent if slightly prolix ‘sacred song’ with an organ accompaniment such as Ives most likely performed during his years as church organist.

Among the most attractive of Ives’s earlier songs, Far in the Wood (1900) sets an anonymous text that tells of pleasant anticipation with a deft and appealingly ingratiating wit (see also Volume 4, track 19, Naxos 8.559272).

Setting an impassioned verse by Lord Byron, A Farewell to Land (1909) is one of Ives’s most rigorous songs in its highly nuanced vocal line and a piano part that descends across the length of the keyboard.

A setting of Ludovico Ariosto’s pithy verse, La Fede (1920) is among the most concentrated of all Ives’s songs, with its forcefully rhetorical vocal line complemented by piano writing as tensile as it is unyielding.

In its expressive vocal line and seamlessly flowing accompaniment, the setting of Hermann Allmers’ Feldeinsamkeit (1898) suggests Ives was familiar with songs by Liszt; as also in the way phrases are repeated so as to heighten their emotional impact (see also Volume 3, track 20, Naxos 8.559271).

Flag Song (1900) sets Henry Strong Durand’s stirring paean to Yale University with a rhythmic robustness and expressive directness that is never less than appropriate if perhaps occasionally tongue-in-cheek.

Taken from his sacred cantata The Celestial Country, Ives’s setting of Henry Alford’s Forward into Light (1902) contrasts an initial restraint with vocal and piano writing of some elaborateness towards the close.

The setting of an anonymous sonnet “in the Italian pattern”, Friendship (1898) unfolds its belief in this quality as being the pre-condition for love with a forthrightness that Ives’s music thoughtfully underlines.

Another setting of Heinrich Heine, Frühlingslied (1898) enhances the wistfulness of its text with music whose poise and keen dovetailing of melody and accompaniment again point to lessons from the Austro- German Lieder tradition well learnt (see also Volume 3, track 11, Naxos 8.559271).

Justly regarded as among the most significant of all Ives’s songs, General William Booth Enters into Heaven (1914) draws on Vachel Lindsay’s already highly provocative and richly illustrative text as the basis for a eulogy of uninhibited verve and startlingly wide expressive range that between them encapsulate the composer’s avowedly Transcendentalist spirit as well as his questing, Utopian vision.

In total contrast, God Bless and Keep Thee (1898) is a straightforward and yet ardent avowal of love whose sacred undertones are deftly underlined in Ives’s movingly restrained setting of this anonymous text.

Another love-song that has a distinctly sacred tinge, Grace (1900) is also appreciably more intimate in its limpid and serene setting of another seemingly anonymous text (see also Volume 6, track 25, Naxos 8.559274).

Taking as its basis the famous poem by Rupert Brooke, Grantchester (1920) is a song that, with its widely-spaced piano chords and allusion to Debussy, also its underlining of references to classical mythology, is as much a portrait of Ives the composer as it is a setting of the text.

Setting Anne Timoney Collins’s text “in a half-boasting and half-wistful way”, Ives invests The Greatest Man (1921) with sentiments that point unerringly to the reverence in which he held his own father.

Another setting of Heinrich Heine, Gruss (1898) draws from the lyric poem music of appealing simplicity, and features a piano interlude that undemonstratively links its two verses (see also Volume 6, track 32, Naxos 8.559274).

Richard Whitehouse