Audiophile Audition

Lee Passarella

November 5, 2013

Iranian-American composer Reza Vali (born Ghazvin, 1952) has been called the Iranian Bartók. This is apt not because his musical style is especially influenced by Bartók (in fact, Vali claims among his influences Wagner, Mahler, and Debussy, and I detect others as well) but because like Bartók, he’s a dedicated student and cataloger of folk song. Like Bartók, Reza includes not only original folk material but what Bartok’s biographer Serge Moreux dubbed “imaginary folk music.” As with Bartók, Reza’s goal seems to be the assimilation of the folk materials of his own region to such an extent that it is seamlessly integrated into his own musical idiom.

As in the case of the Hungarian master, it’s nigh impossible for the untutored listener to distinguish actual folk melody from that manufactured by the composer himself. The foremost project in which Vali explored Iranian folk music in this way is his series of folk song sets, commenced in 1978. These treatments employ voice and a variety of instruments, either grouped or alone, although Folk Song Sets 9 and 10 are purely instrumental. The two contained on this program, No. 8 and No. 14, are scored for mezzo-soprano and chamber orchestra.

Folk Song Set No. 8 of 1989 was written in memory of Vali’s grandmother, and the central texts deal with lamentation, though by way of variety Vali includes a popular Iranian children’s song, a love song, and a wordless sacred song. There’s textural variety as well in that the love song and sacred song have a chamber-music intimacy, the love song accompanied only by tuned glasses and the sacred song, by notes at the top of the piano keyboard and the claves (a set of wooden dowels struck together to produce a clacking sound—you’ve heard them in music of the Caribbean). In both cases, the effect is ethereal, the accompaniment recalling the sound of wind chimes. That contrasts with the two “Laments,” the first and fifth numbers of the set, which introduce the Tristan chord, “a symbol of love and death” in Wagner’s tale of the star-crossed lovers Tristan and Isolde. Oddly and intriguingly, the children’s song (second in the set) employs Sprechstimme, brittle percussion, and the eerily off-kilter combo of piccolo and bass clarinet—a strangely Expressionist setting for the nonsense text that makes up the song.

Vali, whose musical education began at the Teheran Music Conservatory and was completed with a Ph.D. from the University of Pittsburgh, consciously merged Middle Eastern and Western musical influences in his music, though he came, through a study of traditional Persian music, “to the conclusion that Western equal temperament is a limited system that has already reached its limitations.” He, therefore, turned for inspiration to the Dástāgh/Mághām system employed in Persian music, a modal and microtonal system at odds with the notion of equal temperament.

I suppose that Folk Song Set No. 14 of 1999 is transitional in that the singing of the first song, “The Road to Shiraz,” sounds very Eastern and reminds this listener, at least, of the vocalizations of a muezzin. But the second song, the really tipsy-sounding “Love Drunk,” makes me think—in its jazzy percussiveness—of an Iranian Leonard Bernstein! Ditto, the even livelier “Imaginary Folk Song” (No. 4 of the set). Most of the poetry in this series centers on romantic love, so it’s a surprise to find the last song, “Mountain Lullaby,” is a lament of a mother who wishes her baby calm sleep and protection from some unnamed “suffering / without an end.” But then surprise is one of the elements that Vali supplies with frequency in these folk song sets.

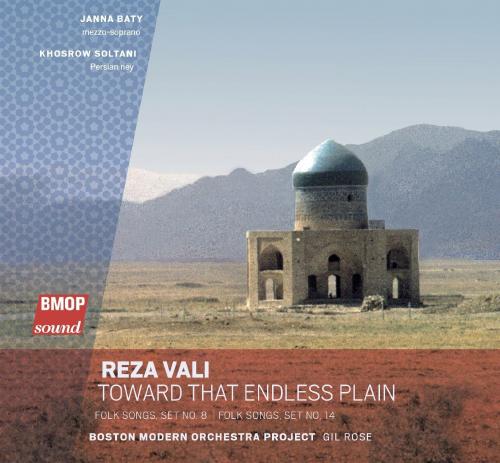

Toward That Endless Plain, a concerto for the traditional Middle Eastern vertical flute and orchestra, is one of those works that fully represents Vali’s employment of the Dástāgh/Mághām system, though again the union, or rather clash, of Western and Eastern musical materials fuels the work. The piece starts with a wild, crashing, highly chromatic introduction for the orchestra that melts into the strange, quietly resonating music of the amplified ney. At this point, the sound of the ney and the orchestra seem to meld, though elsewhere the two diverge in ways that create an animating tension in the piece. The program of the concerto derives from a poem by twentieth-century Persian poet Sohard Sepheri, which speaks of a mystical life journey “Toward that endless plain / That always / Is calling me to itself.” The prelude to Vali’s concerto, entitled “The Abyss,” is supposed to convey “the abyss of the human ego. . /fear, terror, violence, and war”—war represented by a siren blast that ends the prelude. The rest of the concerto concerns a spiritual progress toward a “mystical state of Kamâl (Nirvanâ), referred to in the last stanza of the poem. . . .” The quiet conclusion of the work might, indeed, suggest that a state of inner calm has been achieved, but along the way, the exciting Ecstatic Dance (the second movement) is for me the high point of the work.

This is all very attractive, very appealing music, music in which the exotic and the familiar merge in ways that constantly engage. As usual, the virtuosic members of the Boston Modern Orchestra Project are superb. They’re called on to produce some fairly unfamiliar musical sounds here and there throughout this program. (They become, briefly, a legion of softly buzzing bees, or so it seems, at the close of Vali’s Toward That Endless Plain.) The recording, too, is mostly very good, though fine mezzo-soprano Janna Baty is miked a bit closely for my taste, and in the folk song sets, the perspective is rather two-dimensional. Though the same venue—Jordan Hall of the New England Conservatory—was used for all sessions, the sound in the concerto seems more appealingly open to me. A small matter, really, given the chance to hear the work of this unusually gifted contemporary composer.